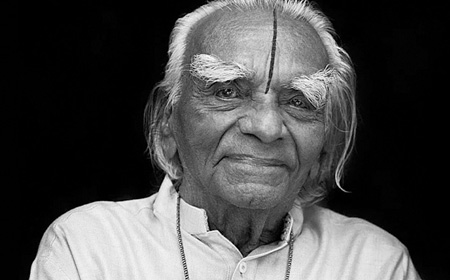

Here at Iyengar Yoga London we are immensely proud of our historic association with B.K.S Iyengar, who was instrumental in the founding of our centre.

Occasionally throughout history there have been individuals whose achievements leave a positive mark across the entire world. B.K.S. Iyengar (1918-2014) was such a person. In 2004 he was named by Time Magazine as one of the hundred most influential people in the world. His fellow Indian, Mahatma Gandhi declared, “We must be the change we wish to see in the world” and Iyengar lived according to a similar principle through his lifelong practice, study and teaching of yoga. His approach to yoga had nothing to do with either mere physical flexibility or New Age spiritualism.

“Example is all, and when example expresses truth, it has the power to transform others.”

B.K.S. Iyengar

Early life

Born on 14 December 1918 to a poor Brahmin family in the tiny village of Bellur, in Karnataka, South India, Iyengar’s beginings were far from auspicious. The eleventh of thirteen children he was born sickly to a mother suffering from the influenza then rife across the world. His schooling was limited due to a series of childhood illnesses including typhoid, malaria and tuberculosis. His father died when he was nine years old and continued ill-health, malnutrition and poverty left him at fourteen with a low life expectancy. He was so stiff that when he bent over to touch his toes, his middle fingers only reached his knees. It is easy at the end of a life to impose a shape and a trajectory which belie its lived reality. The odds were against Iyengar reaching adulthood, let alone the extraordinary age of ninety-five having become the greatest exponent of yoga the world has yet seen.

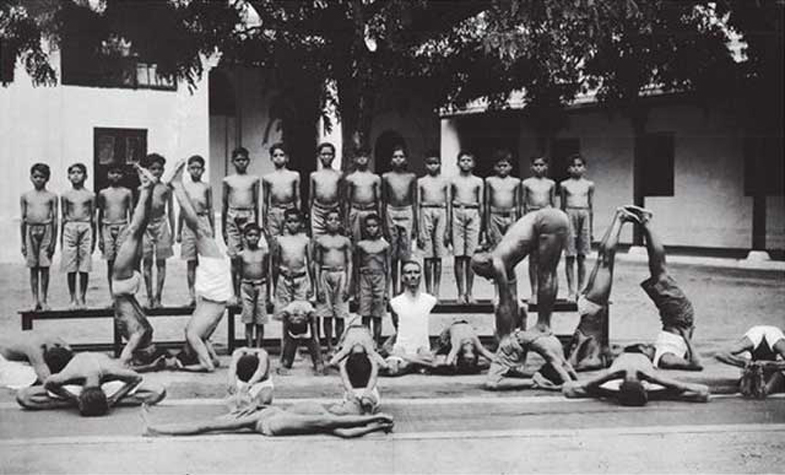

Krishnamacarya's Yoga Shala in Mysore in the 1930s

Training with Krishnamacarya

Under the tutelage of his brother-in-law and guru the venerable yogi Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacarya in Mysore, the young Iyengar had little choice but to take up yoga for the sake of his immediate physical health. In the beginning it was a question of mere survival as his apprenticeship was rigorous, uncompromising and fierce. At the age of 18 in 1937 he was sent far away from his family to Pune, near Bombay as it was then called. By this time determined to devote himself to yoga, Iyengar made a personal wager; he vowed to understand the subject of yoga or die in the attempt. Nonetheless he refused to become a sanyasin (a renuciate). Instead he chose to remain an ordinary householder, later marrying and raising a family. Practising up to ten hours a day he earned only a meagre living from his teaching and often went hungry. A film of his practice in 1938 shows the fluid and extraordinarily fast movements between poses.

Gradually he realised that such a practice was only possible for younger fit people and tended towards inaccuracy. So Iyengar began to slow down his practice to explore every aspect of each asana. This was the beginning of a comprehensive investigation which would lead to a worldwide transformation of the subject.

Friendship with Yehudi Menuhin and first visits to the West

One of his most famous pupils was the world renowned violinist Yehudi Menuhin, who came to study with Iyengar in 1952 because he had reached a crisis in his playing. They became lifelong friends and Menuhin invited him to teach in the West. In recognition of the profound benefits Menuhin derived from the practice of yoga, he would later describe Iyengar as “my greatest violin teacher.” In the 1960s an enlightened educator asked Iyengar to teach yoga for the then London Education Authority. This turned out to be a highly influential programme and established the UK as the first and still pre-eminent base for Iyengar yoga outside India.

The Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute

By 1975 Iyengar could afford to design and have built his own place of teaching, the Ramamani Iyengar Memorial Yoga Institute (RIMYI) in Pune, named after his wife Ramamni who had died suddenly in 1973. From then on until his death he lived and taught there with two of his children Geeta and Prashant. Recently his granddaughter Abhijata has also taught there, and RIMYI has been at the heart of what has become known as Iyengar yoga. As its founder, he personally devised and oversaw the rigorous and lengthy teaching programme which has to be undertaken by students wishing to teach in his name. There are now several thousand teachers of Iyengar yoga working individually and in over 1800 institutes in 40 countries. When recognition began to come from all over the world Iyengar was delighted. With characteristic wit he pointed to the celestial reach of yoga when a star was named after him in 2001.

Ethical and sincere practice

But he never courted celebrity nor was he interested in creating any kind of cult. “Yoga is my way of life,” he explained and when people came to learn from him, he accepted them as his pupils. What he demanded from the thousands of students and especially those who taught in his name was an ethical and sincere practice. “The popularity of yoga and my part in spreading its teachings are a great source of satisfaction to me,” he declared. “But I do not want widespread popularity to eclipse the depth of what it has to give to the practitioner.” Yoga, he always insisted, should be hard work. His teaching was exacting and focused as he drew the best from his students.

“Yoga is my way of life.”

B.K.S. Iyengar

Beat, Kick & Shout Iyengar – a world class teacher

But Iyengar also had a mischievous sense of humour, announcing at one of his Keynotes how people had thought that his initials BKS (Bellur Krishnamacarya Sunderaja) actually stood for Beat, Kick and Shout because of his hands-on teaching method. His charismatic, world class teaching is well documented from various famous individuals to regular small groups to conventions where he taught up to 1000 people in masterclasses. He taught at large events well into his later life including Crystal Palace in 1993, at the age of 86 in Estes Park, Colorado in 2005, and even continued into his nineties with events in Moscow in 2010 and at the age of 92 in Beijing 2011. In China a commemorative stamp was issued in his honour.

That he could carry on teaching until his mid-nineties and with such energy and insight was remarkable and inspirational. For the million and more people who have been taught by him directly, his teaching has genius. He was known to his students as Guruji, one who brings light where there is darkness. Pervading his teaching was a lifelong dedication to a genuinely radical vision of the potential significance of yoga for all.

A yoga revolutionary

In private Iyengar was a conventionally conservative Indian, true to the culture and spiritual beliefs of his Brahmin heritage. As a yogi, however, he was a revolutionary. When he was a young man yoga was still very much an oriental mystery passed on from guru to sisya (pupil), a closely guarded secret kept only for a select group. That yoga came out of India, Iyengar was in no doubt, but he refused to believe that it belonged to any single country or culture. He vehemently and successfully opposed the attempt to patent yoga poses which took place in India in 2011. Yoga, he felt, should be available to any person, irrespective of sex, race, class or creed. It is a “practical philosophy to be experienced”, he maintained, not just “a matter to be described, discussed or debated.”

Light on Yoga

In 1966 he published ‘Light on Yoga’ to bring yoga out from the darkness. There he demonstrated through photographs over 600 asanas which he described in detail with their benefits. This groundbreaking book has been translated into over 22 languages and remains an essential for anyone seeking an introduction to the subject. Light on Pranayama (1984); Light on Life (2005), his yogic autobiography Yaugika Manas (2008), an exploration of the yogic mind – these are only some of the almost twenty books in which Iyengar explored aspects of the vast subject that is yoga. There are also hundreds of articles, lectures and interviews now published. This is an astounding achievement for a man who left school at fourteen with no qualifications.

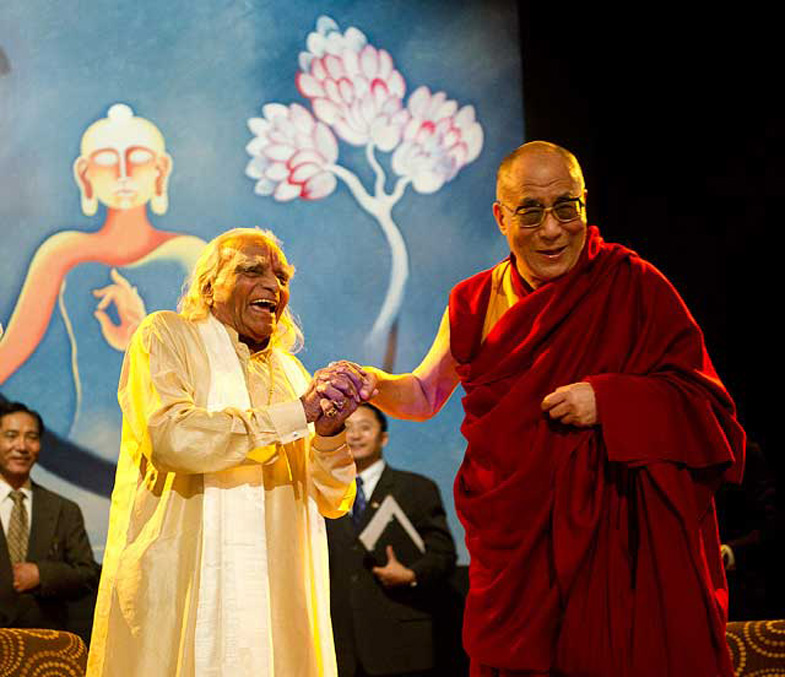

The Bellur Trust

It is certain that Iyengar has made millions from or rather for yoga. Until the end of his life he remained at his Institute in Pune, teaching and learning. “Yoga gave me life,” he humbly maintained and with the money he set up the Bellur Trust, through which the village of his birth was provided with water, electricity, schools, a college, a hospital and in May this year, a Technical Training Centre. He also inaugurated the first temple to the ancient Sage Patanjali there. Patanjali is credited with codifying in Sanskrit the 196 sutras on which yoga is based. Iyengar published ‘Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali’ with an introduction by Yehudi Menuhin in 1993 and ‘Core of The Yoga Sutras: The Definitive Guide to the Philosophy of Yoga’ in 2012 with a forward by the Dalai Lama.

Recognition in his lifetime

India recognised Iyengar’s outstanding contribution to India by awarding him the Padmashri Award (1991), the Padmabhushan (2002) and in 2012 the prestigious IMC Juran Quality Medal, an award given to ‘individuals who have contributed as a role model – in spreading awareness and quality focus in their walk of life’. Iyengar is one of only two non-industrialists to receive this award. Also in 2012 he was voted one of the fifty greatest Indians after Gandhi in a country of over 1.22 billion people. As recently as April 2014 he went to Delhi to receive the Padma Vibhushan, the second highest civilian award in the Republic of India. Interviewed after the ceremony Iyengar declared with characteristic humility, “In life, we have a lot of responsibilities. It is not meant for renunciation. We live in this society and it is our duty to give back to our society. Renunciation comes to me when I am 96. Renunciation means giving up the enjoyment of worldly happiness. But I am full of inner happiness.”

Bringing the science and art of yoga to the West

More than anyone, Iyengar is responsible for bringing yoga from the East to the West. Today there are sadly but inevitably people who have tried to commodify yoga. Iyengar always encouraged personal resourcefulness in using what was to hand in the teaching of yoga. When he realised that some people were unable to do the classical asanas, Iyengar used whatever was around to assist them; in the beginning it was a household object such as a pot, a brick, a piece of rope. In earler years he was ridiculed for this in India and called a ‘furniture yogi’. Yoga equipment like that for any sport or exercise regime is now a multimillion pound industry but to have the t-shirt, the mat and the equipment is to miss the fundamental point. Yoga is a process not a product. What underlies the activity of yoga is a science and an art which require years of careful and dedicated self study and practice. Good physical health is one of its results but peace of mind and serenity in the face of adversity and old age are its true gifts. All too often yoga has been wrongly allied to physical flexibility and this is to diminish its power. ‘The pains that are to come can and should be avoided.” (‘Heyam Dukham Anagatam’, Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, II,16).

Remedial and therapeutic yoga

Iyengar realised that we can do much to strengthen ourselves against disease through the practice of yoga while we are well. When we are ill we can do much to reduce or even eradicate a disease. At the RIMYI Institute and beyond, Iyengar worked alongside Western doctors to search for ways to combat illness by actively involving the patient in the treatment of their illness or medical condition. “My compassion is merciless,” Iyengar explained, “I fight with the affliction not with the person. Therefore, I am merciless with my mercy.” Western medicine is now taking Iyengar’s pioneering work seriously. Much of his remedial and therapeutic work has been published, and many trials and scientific studies have shown extraordinary results.

Meeting with the Dalai Lama in New Delhi, on November 20th, 2010

A student of yoga to the end

For Iyengar it was never a question of East versus West but of the knowledge of East and West being combined for the good of humanity as a whole. In his international outlook Iyengar had much in common with the Dalai Lama with whom he had a public dialogue in 2010. Iyengar never retired. “I am a student of yoga,” he would repeatedly explain and spent over eighty years revisiting the first principles of the vast subject that is yoga. For many it is this willingness to continually re-engage and revisit the practice of yoga that shows the mark of genius. The combination of the extraordinary and the ordinary in BKS Iyengar’s own definition of the Yogi is a fitting description of the man himself as well as an enduring inspiration to others. ‘Even though he possesses an inner knowledge of such depth and subtlety that he visibly lives in a state of exalted wisdom, he also visibly lives with his feet planted firmly on the ground. He is practical and deals with people and their problems as and where they are.’

On 14 December 2015, BKS Iyengar’s birthday, Google celebrated his achievements by featuring him as the Google Doodle on their home page. A fitting tribute for a man who was renowned for his remarkable teaching performances, he was able to give the largest ever live Iyengar yoga demonstration to Google users across the globe post-humously.

This obituary was written by Penny Chaplin and Nathalie Blondel. It was approved by Dr Geeta S. Iyengar and circulated to the UK press.