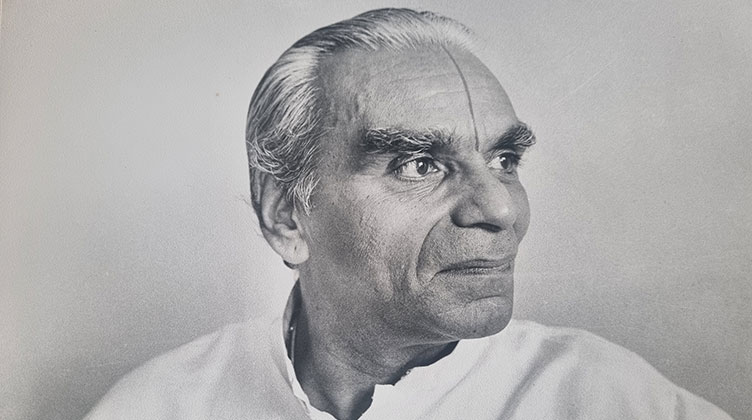

Below are extracts from a speech given by BKS Iyengar in 1984 at the opening of what was then called the Iyengar Yoga Institute in Maida Vale, known today as Iyengar Yoga London. BKS Iyengar’s words convey how important it was to him to have established a yoga centre in London as a hub from which the benefits of the practice could be spread far and wide. He also describes his expectations of his students and the profound and practical wisdom of the yoga sutras of Patanjali.

“As you are all aware, today’s function is just a formal one since the Institute has been open for several months. It is the official opening just because I am here.

You know, it is a great joy for me to see a place outside India, a centre in London, because when I first visited the West, I planted this seed of yoga originally in London, which is the cultural centre of the entire world. It is here that the seed has sprouted and reached all corners of the world.

Many Indians travel to the Ganges to take a bath as it is considered to be the holy water of the East. It has been said that I come here to take a bath in the Thames in order to purify and culture the people of England in the knowledge of yoga, and to remove the misunderstandings that take place even amongst my own pupils.

In one of the yoga sutras of Patanjali he gives the advice that one should be friendly, compassionate, delighted at the progress of others and indifferent if some people do not wish to improve at all. I feel that this advice should be taken to heart by all of us, including me, since we are all human beings and we all make mistakes. Sometimes even I make a mistake, but fortunately my mistakes may be pardoned because they are all minor.

I came to London more than twenty times and many of you do not know the struggles of my early life, even in London, though you have read Body the Shrine, Yoga thy Light (BKS Iyengar, 1978). How many of you know that I used to walk nearly six or seven miles every day to present yoga in London? My life was not a smooth flow even in this country. Every day I used to get up at about two o’clock in the morning, finish my yoga practice by about four-thirty, leave Hampstead at five, walk to Highgate to teach, then walk to Kentish Town to teach, from there take a bus to King’s Cross and from there walk to Caledonian Road to teach. So, you can just imagine what a hard struggle I had to present this great art so that it would grow in this country. Today it is handed on a silver plate to many of you. You are all my students now, but if I had not worked like that in those early days probably nobody would have been doing yoga today. But I put up with all the hardships hoping that one day this cosmopolitan city of London would present this art to the world as if it was seeded in London, though I come from India. To a very large extent I have succeeded, because from here it has spread to all the five continents, first to America, then Africa and last year I conquered Australia, and even far Eastern countries, such as Japan, have taken to yoga in a big way. If I take the entire world, then probably millions are following the way in which I taught, though twenty and thirty years ago I was walking from Hampstead to Highgate and Kentish Town.

it is a great joy for me to see a place outside India, a centre in London, because when I first visited the West, I planted this seed of yoga originally in London, which is the cultural centre of the entire world. It is here that the seed has sprouted and reached all corners of the world.

So, if a single person can build up so much, you also should struggle to pass on this art in pure form. The responsibility on you people today is enormous. Sometimes I feel that if I had been selfish from the early days, then perhaps I would have had many selfless pupils, but because I was selfless from the beginning, many of my pupils have become selfish. I am saying this deliberately, because now that there is an Institute, there is a tremendous responsibility to maintain the good name of yoga and to carry the message of yoga to all people, [those] who can afford to pay and those who cannot.

Two and a half thousand years ago, Lord Buddha said that the greatest thing in the world is to give health, but the greatest of all great things is to give spiritual health. Today I think this saying has to be reversed, and to give physical and mental health is the greatest service to the world, because without these, spiritual health cannot come. There is a very good definition in the Kathopanishad that the body is a chariot, the organs of action and perception are the horses, the intelligence is the rein and the one who holds the intelligence is the rider. If there is a disturbance in the chariot, then the charioteer cannot control the horses. If the charioteer is skilful, but his chariot is not good, then his skill has no value at all. And it is said that the chariot, which is the body, and the horses, which are the senses, are controlled by the intelligence, the rein. Then the dweller in the body and the dwelling place, the body, both can realise the soul, which is as small as the head of a pin and as vast as the universe.

Now, I will give the background about Patanjali, of whom you have all heard. Patanjali was a great sage and is regarded as the father of three disciplines – grammar, yoga and medicine. He is a svayambhu, a self-incarnated person, who took birth of his own accord. Through his insight he saw a lady who practised tremendous yoga and dance; he wished to accept her as his mother. The yogini was unmarried and had no children. She prayed to the Sun God: “On this earth I got this knowledge through your light. As I have no student to pass it onto, I give this knowledge back to you through an oblation of water.” She took water in her hand as oblation and was just about to pour it away when she saw something moving. It was a small snake which took human form; that was Patanjali. Pata means fallen, anjali means prayer. So, Patanjali means that which fell at the time of prayer. Pata also means snake. That is why Patanjali is always depicted as being half human, half serpent.

Patanjali first translated and wrote a commentary on Panini’s grammar. Then he studied dance, and after learning about the movements of the body, of the muscles and joints and so on, he wrote a book on medicine. Then he thought, ‘I have written two works but I have not touched the mind at all.’ That is why the first chapter of the Yoga Sutras commences with the mind. Then, after writing about the mind in the first chapter, he thought, ‘I have jumped to the mind without giving the foundation’, so he gives that in the second chapter, starting again from the body. Then he deals with how to face the various sufferings and sorrows of life through the eight aspects of yoga: yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana and samadhi. He then goes on developing from the body to the mind.

Many people have read that you can sit in any comfortable pose and meditate. Patanjali never said that. ‘When effort ceases in an asana, that asana is mastered and you become one with the infinite’, so the sutra says: Prayatna saithilya ananta samapattibhyam (Y.S. 2.47). At that time the asana is perfected. When both body and mind reach a certain level of stability, the dualities of personality and thinking come to an end and there is no difference between body, mind and soul.

When that difference disappears, then Patanjali says that the external organs, which were always dragging the soul, using it as an instrument for their pleasures, now become servants of the self. Having enjoyed worldly life through bringing the self in contact with the senses, now the senses realise through analysis that they were dragging you on the wrong path and they follow you instead. Then only the moment of kaivalya, freedom, is attained. Till then there is no freedom.

So, in order to achieve that freedom and beatitude, that balance between mind and body and soul, these eight aspects of yoga have been given to you. All in various ways and means and with various teachers.

there is a tremendous responsibility to maintain the good name of yoga and to carry the message of yoga to all people, [those] who can afford to pay and those who cannot.

You have the responsibility now to see that the lamp of this art is kept burning and everlasting. To keep it burning everlastingly involves not just teaching but tremendous practice in you, tremendous humility in you. Patanjali says, ‘Avidya, asmitā, raga, dvesha, abhinivesha kleshah’,the afflictions or hindrances to spiritual practice are ignorance, pride, attachment, aversion and clinging to life. When you have reached a certain stage in your evolution, due to some want of spiritual wisdom, pride may enter you. So, he says, learn humility in place of pride, learn spiritual knowledge in place of technical knowledge. Be aware of the happiness which creates desires, be aware of disappointments which bring malice and at the same time transform people into other than what they are. All these are due to attachment to oneself and to the fear of death. If when you are doing yoga, you learn to understand the svarasa vahini, the self-energising energy, which flows in your body, then sorrows will never touch you.

With regard to sorrows, in the first chapter Patanjali speaks of the fluctuations of the mind and in the second he speaks of the sorrows which come through the contact of the senses with the mind and the body. Both lead to the same, that is, to suffering. So, to stop these sorrows, to stop these fluctuations, the method is only these yogic practices. When you acquire by these practices freedom from worldly desires, Patanjali does not say like others that you should renounce this happiness which does not breed desires. He says, rather, that you should watch yourself, and that that happiness in which you are not caught up in desires is a pure happiness. But if you get caught up in it, remember that you are inviting sorrows, for desires bring sorrow. It is a vicious circle – you create desires and the desires bring sorrow.

while doing an asana you have to show friendliness to the strong side, compassion to the weaker side, delight on the side that is doing well and indifference towards non-success. In teaching and practice, one may be a little higher or a little lower, but in front of God we are all the same. We are all children of God, and as such we are all sisters and brothers. Therefore, there should be no seed of ill-feeling towards one another.

If you can balance these two (sorrows and happiness) and understand the life energy which flows in your body in the form of consciousness or intelligence, and if there is no variation in the flow of your intelligence in the self, no difference between mind and body, then Patanjali says that life and death are one. As life and death are one, so one is free from fear of life and fear of death. So, you have to develop these things, and also to develop the qualities of friendliness, compassion, delight and indifference, as Patanjali says in the 33rd sutra of the first chapter (maitri karuna mudita upeksanam. This mean that while doing an asana you have to show friendliness to the strong side, compassion to the weaker side, delight on the side that is doing well and indifference towards non-success. In teaching and practice, one may be a little higher or a little lower, but in front of God we are all the same. We are all children of God, and as such we are all sisters and brothers. Therefore, there should be no seed of ill-feeling towards one another.

London was the starting point from which yoga grew to such an extent. It should also be the starting point for yoga to become harmonious to one and all. See that like a sapling you take care of it so that it grows into a gigantic tree bearing fruits and flowers. I taught in London first, so I want this Institute to be a feeding centre of yoga to other centres, not only in Great Britain but also in other places. There should be two centres: Poona [Pune] and London. Those who can come to Poona are welcome; those who cannot come to Poona should come to this Institute. And in order to maintain the Institute each one has to carry a tremendous responsibility. So please help each other. See that this Institute in London develops in such a way that everybody should say that the moment you come here there is a tremendous glow, a tremendous light. God has graced this area and blessed it, otherwise it could not be so bright. It is only we who have not got that grip to accept this grace which has come from above. So that is why I say, Keep the light burning, and see that the grace does not disappear from you people.”

From Dipika summer 1984, vol.11

Blog categories

Become a member

Join our community to get reduced class prices, early booking for events and workshops plus access to the studio for self practice.

Recent news and articles

Origins of the Modern Yoga Mat

24 October 2024|

2024 Convention – Group Livestream Event

7 March 2024|

The First Public Iyengar Yoga Class in the UK

22 November 2023|

NEW Hybrid Classes

5 September 2023|