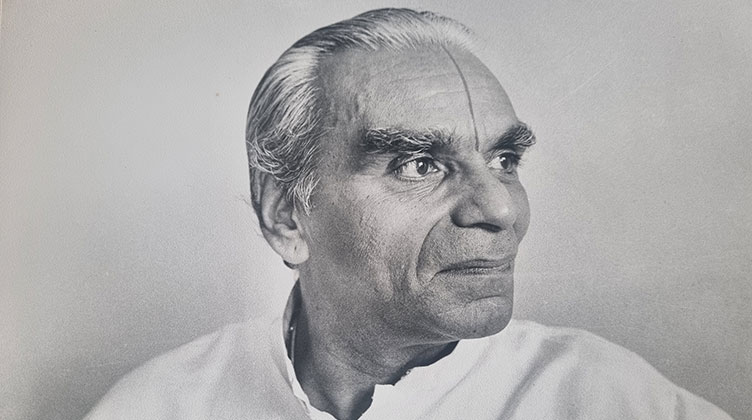

By Alice Chadwick

Many of us begin our practice with the invocation to Patanjali. His statue sits in Iyengar Yoga London’s large Maida Vale studio, one of the few objects other than props in the room. Like the birds in the garden or the rain on the roof, it lends its calmness to our space. Here we can put down the things of daily life and pick up the tools of yoga. But why this particular sculpture? Where did it come from and why is it on a plinth in the corner?

The Statue is Commissioned

The statue was bought in Bangalore, India for the first Institute building in London, founded at Maida Vale in 1983. The following May, the carving was blessed in a private ceremony with BKS Iyengar. Almost a decade later, Guruji was again at Maida Vale for the dedication of the new building (1993). The statue was garlanded with marigolds and carnations, Guruji recited the invocation and a priest performed a puja (ceremony of dedication and devotion). On completion of the building (1994), a photograph of Guruji in Padmasana was placed on one side of the glass doors and the sculpture, on a high shelf, on the other.

November 1997: Mr Iyengar attended the official opening of the new Institute

It was his last visit. A puja was again performed in front of Patanjali but Guruji was unhappy to see the idol on its high shelf. It must be on a pedestal, he insisted, at eye level, connected to the earth and facing northeast. And so Patanjali came to be placed where we see him today, both raised and earthed by a plinth, as Mr Iyengar required.

Lord Patanjali

In the statue we meet Patanjali in his mythic form: the incarnation of the Serpent-God Adisesa. According to legend, Adisesa witnessed Shiva’s cosmic dance and was moved to become his follower. Searching for a human mother, he saw Gonika, a learned yogi, praying for a child to pass her knowledge to. She scooped up an offering of water and Adisesa, in the form of a tiny snake, appeared in her hands. She named him ‘Patanjali’, meaning ‘fallen into folded hands’ (from ‘pat’, to fall, and ‘anjali’, hands folded in reverence). Patanjali grew to become a sage of exceptional understanding and was charged by Shiva to communicate his wisdom to humankind.

Half-snake, half-human, the Maida Vale Patanjali sits on his tail with seven cobras’ heads above him. His lower hands make the Anjali mudra, as befits his name and his devotion to Shiva; his upper hands hold a conch and wheel. He bears a red ‘tilaka’ (mark of honour given during puja) on his forehead. Sacred carvings – more properly ‘murti’ (idols) – are traditionally installed by a priest, who infuses them with ‘prana’, or cosmic life force, and welcomes the divinity in.

Carved from hard black granite, the modeling is nevertheless rounded and graceful and the detail finely cut. In this respect, it is a typical Indian devotional carving. This tradition is old and cosmopolitan, with roots in classical Greek and Buddhist sculpture. Carvings of Patanjali date back to the thirteenth century. The statue at Melakkadambur is one example: here Patanjali stands tall on his tail, a tiny dancing Shiva above his head.2

Sage Patanjali

Fused with this divine figure is another Patanjali – the author/compiler of the “Sutras” on yoga. An Indian scholar and yogi (generally placed in the first centuries CE), Patanjali gathered together what had been disparate and unwritten, thereby enlarging and profoundly deepening our understanding of yoga. His text, admired for its wisdom, beauty and concision, provides a solution to the central difficulty of the human condition – how to live well in relation to ourselves, those around us and God. In the Yamas and Niyamas (ethics), the progression from postures to controlled breathing and beyond, the sutras provide a radically pragmatic approach, as BKS Iyengar explained: ‘To comprehend their message and put it into practice is to transform oneself into a highly cultured and civilized person, a rare and worthy human being’.3

According to Geeta Iyengar, Patanjali’s conch and wheel symbolise the wisdom and protection given to us by his “Sutras”.4 The ‘sankha’ (conch) calls us in readiness to practice; the ‘cakrasi’ (wheel/disc-shaped weapon) cuts through our ignorance, ego and other dangers. Patanjali’s snake canopy also embodies his protection, its multiple heads suggesting omnipresence as well as the many ways in which the sutras guide us. The agile, ceaseless effort required of us as students is represented by his serpent’s tail, while its arrangement in three and half coils symbolises, among many things, the three sacred sounds of A-u-m and the three works sometimes attributed to him (on yoga, medicine and grammar), the half coil indicating his complete enlightenment.

The importance of Patanjali to the Iyengar tradition can, then, hardly be overstated. He is the father of yoga, our powerful protector, author of its foundational text and BKS Iyengar’s first and primary teacher. Let us turn now to a man who has dedicated his life to a different sacred art – carving.

Sculptor Padmanabachari

Shri Padmanabachari was born into a family of stonemasons, his ancestors having produced sculpture in the Bangalore region for around eight centuries.5 With many of his children and grandchildren apprenticed to him, the sculptor works in the traditional manner, outside, his stone directly on the earth and surrounded by chippings. The local granite is heavy and resistant; to master large blocks requires physical as well as artistic stamina. Despite this, and his advanced age (he is in his 90s), he works long hours and uses only hand tools. Rough shaping and fine carving are done with hammer and chisel and the idols are finished with polishing stones, emery and water.

Sculptors are considered the descendants of Vishvakarma, architect to the gods, and their sacred task is governed by long-established codes of practice. Specific prayers and mantra are recited throughout the process, asking blessing and drawing the divinity into the stone. As well as these devotions, Padmanabachari emphasises the importance of study. Sculptors must learn Sanskrit, he insists, to better understand the gods they are making. Due to poverty, his own formal education was not extensive but his family was ‘rich in tradition of sculpture’.6

It was BKS Iyengar who first asked Padmanabachari to carve a Patanjali, as the sculptor recorded. ‘He [Guruji] wanted a stone idol of Sage Patanjali made. I was not that comfortable then, as I couldn’t visualize how exactly the sage looked? For that matter, I even didn’t know Guruji then. But out of spontaneity I had agreed […] to make one…. and that was the start of my association with sage Patanjali and of course with Guruji.’ Bellur, Guruji’s birthplace, is a short drive from Padmanabachari’s village. Having heard of him by reputation, Mr Iyengar arrived carrying Sanskrit texts. The two men studied together and an initial drawing was made. This sketch was the basis for the first Patanjali, a statue that took two months to carve. Padmanabachari then made it his life’s mission to carve Patanjalis ‘out of the toughest stones’.

If Padmanabachari was initially unsure what Patanjali should look like, we might imagine that Mr Iyengar – deeply knowledgeable about Patanjali – was absolutely clear about what he required. Some of Patanjali’s attributes go back centuries; others, like the conch and wheel, are entirely new to the Iyengar carvings. They are described, of course, in the invocation to Patanjali: ‘sankha cakrasi dharinam’, he (Patanjali) holds a conch (sankha) and a disc (cakra); ‘sahasra sirasam svetam’, and is crowned by a thousand-headed cobra. The statue brings, then, the poetry of the invocation before our eyes in concrete sculptural form.

Padmanabachari’s first carving was installed in the courtyard at RIMYI, Pune, where it remains a welcoming sight for visitors. To put the Pune and Maida Vale Patanjalis side by side is to be struck by a close family resemblance. It is no surprise to learn then, that after the first Pune sculpture was finished, a new statue was commissioned from Shri Padmanabachari. This Patanjali – the Maida Vale carving – was shipped to London in a wooden crate; on arrival, its considerable weight surprised everyone.

Yoga & Carving

As a yoga teacher learns to read a body, to see beneath its surface and see with compassion, so a sculptor learns to read stone. ‘We are specifically taught how to identify and then be friendlier with the material we choose,’ Padmanabachari has explained; ‘there is a unique way to test the right stone especially for the idols, even before we hammer our first chisel on it. This kind of knowledge […] comes only from experience’. The sculptor must see the deity in the stone and find a way to bring it to life. The courage required to progress is significant – there are risks to the sculptor as well as to what he creates. Padmanabachari himself drew a comparison between the rigorous determination required by his art and that displayed by Mr Iyengar who, particularly as a young man, pushed himself to the physical and mental limits of what is possible in yoga.7

Equally striking is the comparison made by Guruji between breath in pranayama and the pneumatic drill, a tool used in quarrying stone.8 Both are at once powerful and dangerous; as well as courage, both require wisdom and control. ‘Every stroke of our hammer is an act of responsibility’, Padmanabachari has said, a comment equally applicable to the teaching and practice of yoga.

If there is a kinship between making sculpture and teaching yoga, there is another between the statue in our studio and our practice of yoga postures. Seated comfortably on his coils, Maida Vale’s Patanjali is, in a literal sense, in a yogasana (the word ‘asana’ means seat). This compact, stable pose, together with his symmetrical upper body and benign expression, embody one of Patanjali’s own great yogasutras: ‘sthira sukham asanam’ (‘Asana is perfect firmness of body, steadiness of intelligence and benevolence of spirit’9). The carving’s snake-human form also reminds us that the asanas are rich with the power of animals, plants and gods to shift shape. But perhaps it is in Bhujangasana, cobra pose, when we might think especially of Patanjali. Here we are half snake (legs working together, spine supple and coiling) and half human (reluctant shoulders moving back, chest lifting up). If we begin our practice with an attempt to summon Patanjali’s serpentine fluidity, we end by seeking his unshakeable stability. Through long practice, the body, and ultimately the consciousness, find stillness. The carving’s stately bearing provides an image of this equilibrium, the inner stability that represents Patanjali’s definition of yoga itself.10

The collaboration between the sculptor and the yoga guru was long and productive. They were also friends. Perhaps Guruji recognised in Padmanabachari a fellow traveller: from a small village in southern India, he became a craftsman of great strength and skill, an artist of profound sensitivity and a man deeply committed to his sacred work.

Conclusion

To our opening questions, we can answer that the statue came from a village close to Guruji’s birthplace and was made by the sculptor Padmanabachari. We know of the deep connection between Patanjali and Iyengar yoga, to this we can add the close partnership between Mr Iyengar and the man who carved the Patanjali idols. Together they took up an ancient iconography and gave it new life.

As to why the statue is in the Iyengar Yoga London studio, a number of suggestions can be made. First, it reminds us of the living relationship between Patanjali’s “Yogasutras” and our practice. His disc and conch represent the practical tools set out for us in his text; his metamorphosis reminds us of the suppleness and effort required if, like him, we seek transformation. To inspire our work, the statue provides an image of the perfect asana; in it we glimpse the equanimity of the fully evolved soul. Secondly, Patanjali is present as our protector. He shelters our practice and his writing guides us though difficulties. Thirdly, Patanjali provides the foundation for our knowledge of yoga. The carving reminds us of a legacy of scholarship and teaching that stretches back many centuries.

A final reason: in a recent class, we were instructed to stand up on two bricks in Tadasana. ‘We put a sculpture on a plinth’, the teacher said, ‘to give it importance’. I stood on the bricks feeling remarkably tall. ‘Step down,’ she said. ‘Feel the pull of gravity as you return to earth’ (it felt strong). When we sit down before Patanjali, we step off the pedestal of our egos. We fold our hands and bow our heads, returning his Anjali gesture. Learning requires humility, as Geetaji has taught us: ‘you know that you are very small in front of that greatest soul […] you are “coming down” to learn something. And you can’t learn anything unless you come down’.11 Each time we step down before Patanjali, we receive the opportunity to remake ourselves as students.

My sincere thanks to Penny Chaplin, Jake Clennell, Gerry Chambers, Abhijata Sridhar, Alan Reynolds, Korinna Pilafidis-Williams, Stephen Richardson and Sallie Sullivan for sharing knowledge and images for this article.

References

- Gudrun Bühnemann, ‘Naga, Siddha and Sage: Visions of Patanjali as an Authority on Yoga’, in “Yoga in Transformation”, K. Baier, P. André Mass & K. Preisendanz (eds), Vienna University Press, 2018, pp. 575-622.

- Photo: Raja Deekshithar, 11 Feb 2007, with kind permission of Ian Alsop; http://asianart.com/articles/ratha/28.html.

- BKS Iyengar, “Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali”, p. 1.

- For Geeta Iyengar’s comments on Patanjali: Peggy Cady, ‘Exploring the Invocation to Patanjali’, iyengaryogacentre.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Patanjali-2.pdf.

- For Padmanabachari’s working life and details of his first meeting with Mr Iyengar, I am indebted to Jake Clennell, director of “Iyengar: The Man, Yoga, and the Student’s Journey” (in conversation).

- Blogpost, V. Gayathri, July 9th 2010: http://creative-talk.blogspot.com/2010/. Further comments by Padmanabachari also come from this post, unless otherwise stated.

- For Padmanabachari’s comments on courage, as well as footage of him at work, see the trailer form “Sadhaka”: http://clennellfilms.com/documentary#/doc-sadhaka/.

- BKS Iyengar, “Light on Yoga”, p. 431 (Pranayama, Hints and Cautions, 3).

- “Yoga Sutras of Patanjali”, II, 46, BKS Iyengar’s translation.

- ‘‘yoga chittavrtti nirodhah’’ (‘Yoga is the cessation of movements in the consciousness’), YSP, I, 2.

- In Peggy Cady. pp. 2-3.

This article is taken from Dipika, the Iyengar Yoga London Journal, 2020. If referencing this article, please credit as appropriate.

Blog categories

Become a member

Join our community to get reduced class prices, early booking for events and workshops plus access to the studio for self practice.

Recent news and articles

Iyengar Yoga Home Practice Videos with Raya Uma Datta

27 March 2025|

B.K.S. Iyengar’s visits to Ann Arbor, Michigan

20 March 2025|

Origins of the Modern Yoga Mat

24 October 2024|