Richard Agar Ward is one of the most senior and long-standing teachers at Iyengar Yoga London. Here he shares his yoga beginnings and his first meeting with Guruji with us.

When and why did you start yoga?

I have been asked this question before and I often say, truthfully, that I started becoming interested in yoga because of William Shakespeare. When I say that, people naturally assume that I somehow uniquely found mention of or reference to it amongst Shakespeare’s Collected Works. While it is true to say that Shakespeare addresses some of the same ontological and teleological questions dealt with in the philosophical literature of yoga, the truth of the matter is much more prosaic.

I first became interested yoga in 1970 when I was a schoolboy. I had never heard of it as far as I remember until I noticed a book called Teach Yourself Yoga belonging to a boy who was in the same boarding house at school. The book was part of a series of self-educational imprints popular at the time. The boy to whom the book belonged was none other than a namesake of the Bard of Stratford-upon-Avon, William Shakespeare. For whatever reasons, it was recommended to him that he should take up the electric guitar, at which he became highly proficient (specialising in a passionate rendition of “The House Of The Rising Sun”), and yoga, through the use of this book. William lacked interest in the book, as far as I could tell, and agreed to give me a long-term loan of it, and I read it.

Two things became immediately apparent. First, that yoga was an awesome ancient Indian philosophical and metaphysical system and culture which dealt with all aspects of the human embodiment both gross and subtle and, second, that I had not the faintest hope of being able to teach myself the subject. It was clear that acolytes would need to start with attaining some bodily positions but when I tried a few of them at home in the holidays I quickly became confused and realised I did not know how to make any serious attempt at anything. For an absolute beginner like me it became obvious that teaching myself was out of the question. What progress could I possibly make? For an empirical subject, a language as exotic as Hungarian, for example, a Teach Yourself book was a worthwhile guide, but it seemed unhelpful for anything as practical as yoga. I then resolved that one day I would find some way of taking lessons in the subject. The book made no mention whatsoever of the concept of a “Guru” but it became clear that finding one would be my only chance.

I also had less prosaic reasons for becoming interested in yoga and this relates to the fact that it spoke of both life and death and saw life in this world as part of a continuity. The Christianity I was brought up with seemed very vague on the subject beyond a sort of “jam tomorrow” approach as part of a bargain bestowed in return for belief and commitment. Even at that young age, I felt there had to be something more meaningful. Death had been part of my life. My twin sister died when we were born, for which my mother grieved deeply. As soon as I became conscious of my own thoughts I knew about and thought about death and have continued to contemplate it every single day of my life since, without exaggeration.

I don’t ever remember having been told about my twin. I don’t think I needed to be. I cried inconsolably every single night of my life until I was two, according to my mother, and the local GP suggested it was due to grief for my twin, all other causes having been discounted. Not long after my first interest in yoga, another sister, an older one, died. It seemed to me that you needed a coherent approach to the matter of life and death in order to negotiate life, and yoga seemed to me to be fit for this purpose. Both these things remain true to this day.

How was your first meeting with Guruji?

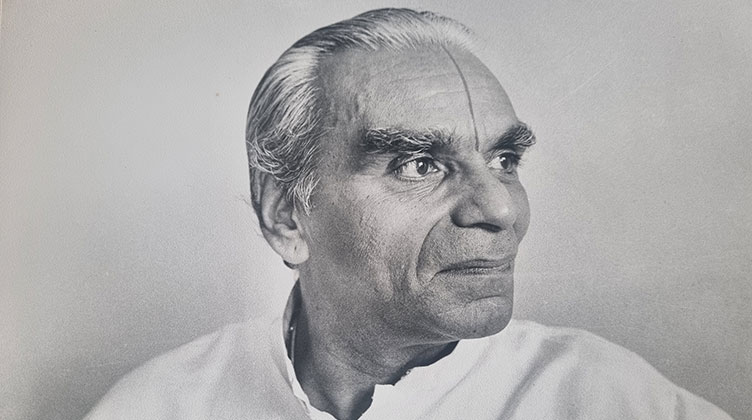

My first encounter with Guruji came in July 1976. He was visiting England on his way back from a visit to the USA and on that day taught morning and afternoon classes at Cecil Sharp House near Primrose Hill and Regents Park in London. I had started learning his yoga in the autumn of 1975, while in my second year at Oxford University. My teacher, Kofi Busia, booked a group of his pupils into the classes. In those days we did not know BKS Iyengar as “Guruji”, a title that gained common currency some ten years later. From the start we pupils attended classes of “yoga as taught by Sri BKS Iyengar”. He was referred to simply as “Mr. Iyengar”, an epithet that seems inadequate now but that was what was used then.

The term “Iyengar yoga” was also yet to be coined. Guruji had already achieved widespread recognition as the author of Light on Yoga, published ten years previously. At that time his remaining remarkable literary output, and worldwide recognition, fame and acclamation, were still to follow. Whatever stature he had then was there to be seen by the people around him, and in much more personal terms, not yet with the modern-day, very famous and public, indeed iconic aura we are now so familiar with.

In those days it is no exaggeration to say that Guruji had a reputation as a strict disciplinarian; this was possibly the most discussed, even the major preoccupation surrounding his teaching. People reacted to this approach in various ways. For some it was very difficult to see that his demands on his pupils were fair. To others, these demands were, on the contrary, not at all personal but a product of his extraordinary devotion to yoga and an insistence that any pupil of his should pay yoga the utmost respect as a divine art and science.

The classes at Cecil Sharp House were somewhat unusual in so far as they not only had participants both morning and afternoon, but an audience of several score as well, who sat on three sides of the very large room serving as the classroom. As I entered the classroom early that afternoon, I encountered my yoga-pupil colleague Phil, who had watched the morning’s class. For some unaccountable reason, so I thought, he revealed a desperate, shocked pallor in his face. “What’s up?” I asked. “He … he’s a madman!” declared Phil, who could say little more beyond this. “Interesting,” I thought to myself, unimpressed and indifferent, as only a 20-year-old can be, “I will have to see for myself.”

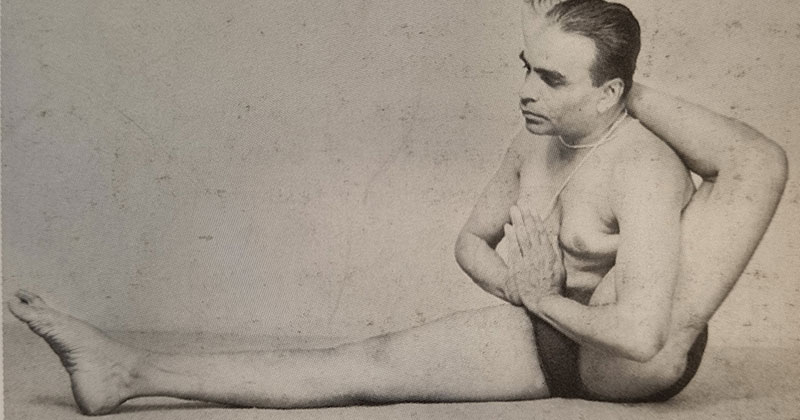

While all the participants roamed around, assembled and prepared in various ways on the floor of the classroom (note that there were no such things as yoga mats or equipment in those days for people to pass their time staking out their territory) there was no sign of Mr. Iyengar. Then, quite unannounced and unobtrusively, he entered the hall at the far end and stopped, head a little raised, without looking at anyone, almost as if he was sniffing the atmosphere. He was garbed in what I thought was a singularly inappropriate, garish Hawaiian shirt resplendent with palm trees. Clearly Hawaii had been a stop on his American tour. For a moment I thought: “Can this be the author of Light on Yoga, in this remarkable shirt?” A moment later he took off his shirt and stood before us ready to start the class. In that split second, I felt I saw him as exactly that author of Light on Yoga and in that moment I realised from deep inside that there was nothing to fear and that I could trust this person completely. To me it was a remarkable transformation before my eyes.

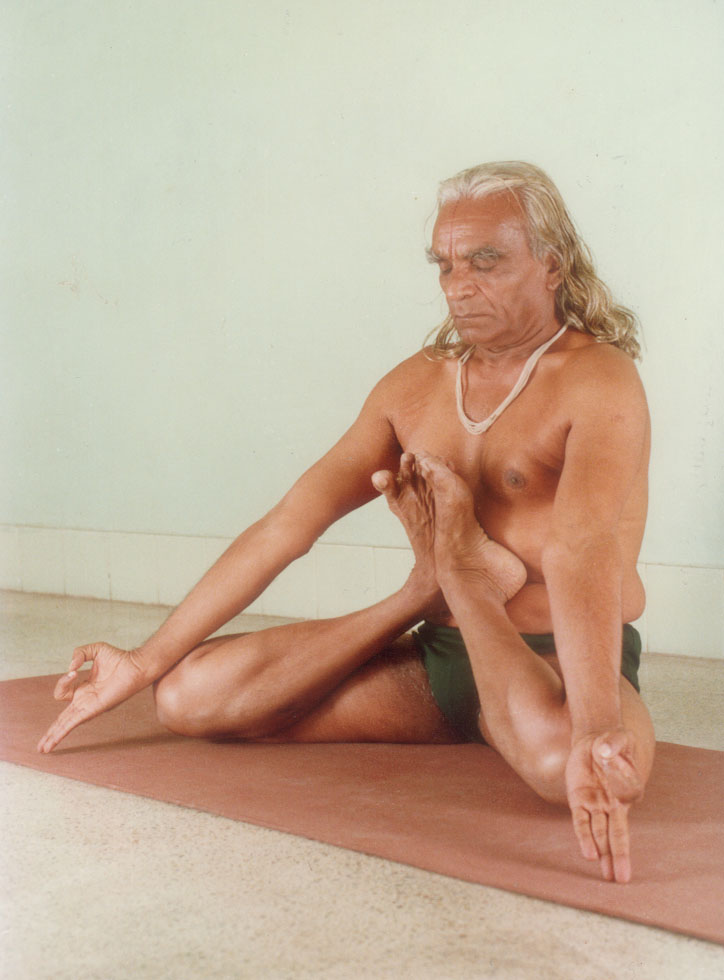

The class lasted some three hours. Guruji combined a remarkable skill and depth of knowledge of the human body with a distinct flair for showmanship, being ever conscious of the audience as well as his pupils. We had the sense of him always reaching out with yoga to as many people as possible. The more people present, the more he reached out. What he taught for us as individuals had a public presentation and we pupils were part of that presentation.

There was of course no hiding place. In Sirsasana everyone who could stay up on his or her own did so, without support. Some teachers were called to give support in the middle of the room to those who could not stay up alone. Not far from where I was wobbling unsupported, and near the end of what seemed a very long time in Sirsasana, a teacher, the late Penny Nield-Smith, allowed her charge to come down from headstand. Guru stormed over. “Why did you let her come down?” he roared. “She was tired,” came Penny’s reply. “She was not tired,” Guruji retorted, and without turning to look (so I was told later) slapped my leg at which point I fell over harmlessly. “He was tired, she was not!” This engaged the audience wonderfully.

During Paschimottanasana Guruji announced to all that while in the pose one could bear any weight on one’s back in the same manner as a horse can carry great loads. He was very close to my legs as he said this and once he finished, he stepped up to stand on my back. My progress was very rapid and complete. “How does that feel?” he demanded. I raised my head enough to exclaim “Marvelous,” which indeed it was. The hall erupted with mirth.

Being taught by Guruji was not without its difficulties. Foremost among these, from my perspective, was my unfamiliarity with the Indian accent and his way of expressing himself in English. While doing Utthita Parsvakonasana he strode over to me and uttered an instruction. I was unable to catch his words at all. I had however caught the dynamics of his teaching enough to realise that it would be near fatal to ask him to repeat himself or to say that I could not understand his accent. In response, I tried to make every adjustment I knew. I failed to make the correct one, of course, so he kicked me on the inside of my bent leg thigh. All I could offer him was a rather pathetic “I didn’t understand.” Off he stalked, kicking this person here and that person there, barking, “Did you understand? He didn’t understand. Did you understand?” It was an episode usually best forgotten but here best remembered.

Without so much as a wall to use as a prop we were orchestrated to do some poses in novel ways. Virabhadrasana 3 was performed in chains with one pupil supporting hands on the back of the person in front and extending one’s back leg on the back of the person behind. Remarkably it worked. I was using Angela Farmer, a very well-known teacher, as my front prop but I forget who my rear prop was!

It is a curious feature of memory that some episodes from that day have remained with me vividly for decades, but other details have been lost in the recesses of my memory archives, perhaps never to reemerge. Nevertheless, I like to think that the memories I have retained are the most interesting and personally resonant. The following year I was in Pune at RIMYI for my first intensive course with Guruji.

The second part of this interview is a slightly edited version of one which first appeared in Beloved Guruji, Mumbai (2016), 63ff, with kind permission of the publishers.

This article was first published in Dipika, the journal of Iyengar Yoga London, Issue No.53, July 2021. If you would like to republish this article, please ask the editor for permission. office@iyengaryogalondon.co.uk

Blog categories

Become a member

Join our community to get reduced class prices, early booking for events and workshops plus access to the studio for self practice.

Recent news and articles

2024 Convention – Group Livestream Event

7 March 2024|

The First Public Iyengar Yoga Class in the UK

22 November 2023|

NEW Hybrid Classes

5 September 2023|

7 Day Visitor’s Pass

26 June 2023|

Geeta Iyengar on Why We Practise Difficult Asanas

26 June 2023|