Iyengar Yoga & Mental Health

Is the mind a figment of the body or the body a figment of the mind? This is the kind of chicken and egg question that keeps me awake at night. An enthusiasm for such questions was partly what led me to the radical psychiatrist RD Laing and made me write a play about him staged at Hackney’s Arcola Theatre in 2015.

Laing was a Glaswegian psychiatrist whose 1960 book The Divided Self challenged the idea that there is a physiological basis to schizophrenia. One of the things he fought against was the rush to medicalisation of mental distress that typically made people feel more threatened, more depressed and more inclined to divide themselves between public and private personas – a strategy that he saw as the founding move of schizophrenia.

Becoming a guru to the flower power generation, Laing was prone to depression himself and took to self-medication in the form of hard drinking. But through much of his adult life in the 1960s and 1970s, Laing was also a regular practitioner of yoga with a keen interest in Eastern mysticism. And yoga was surely the better part of his therapeutic regime – even if a bottle remained close to hand.

Iyengar Yoga helped me make peace with my brain

For my part it was the desire to inhabit my body better and make peace with my brain that brought me to yoga in the late 1990s. Many friends had taken up ashtanga vinyasa, which seemed too high tempo to me. I was looking for something more calming so I went for a class at Iyengar Yoga London in Maida Vale. I vividly remember my first session, feeling noticeably longer after. It was immediately clear this was something that was going to be very good for me – not because it made me feel longer but because it slowed me down and sent me back to a body I now realise I had been trying to escape. More specifically it was the most therapeutically intense experience I’d had at that time since being laid out on a chiropractor’s table and listened to my spine pop as though in a gun battle as the tension locked in my back was released.

The word ‘uptight’ is a good one for those of us who hold too much tension. It is as though in times of stress your body tightens up to protect itself, in particular by squashing the diaphragm and thwarting your breath. An anxious person breathes too hard and too little. But if your body needs to buckle up how come stretching it out doesn’t make it worse? My theory is that it’s because stretching out muscles that want to tighten up tricks the brain into thinking it’s relaxed:’ fake it ‘til you make it.’ The relaxed state of our muscles is soft and loose and when they feel like that it’s much harder to get stressed.

Healthier, more relaxed, more in your body

It’s therefore no surprise to people who do yoga that however it works, it does work. It makes you feel better, healthier, more relaxed, more in your body. That last bit is particularly important as the desire to dissociate yourself from your body was for Laing a common symptom and cause of mental distress. Separating mind and body was also part of the strategy that he saw as typical of what mainstream psychiatry calls schizophrenia. In his view, schizophrenia was a coping strategy born from the attempt to protect your true self by creating a false self, a strategy that drove you further and further from reality and ultimately from your physical incarnation leading to potential psychosis.

Research on Yoga as an Alternative or Supplement to Anti-depressants

Laing’s views were and remain highly controversial, but much of what he fought for in terms of patient centred talking therapy has been subsumed into mainstream practice. Nor did he make any claim that yoga was a psychiatric panacea or cure for grief or despair. But there is increasing academic and medical research to suggest that yoga can help you live with such feelings and achieve mental equilibrium. One such piece of research at the Boston University Medical Centre (Dr Chris Streeter et al, Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 2007, vol 13, 4) concluded that class-based yoga practised at least twice a week with supplementary 30-minute sessions at home worked as either an alternative or supplement to anti-depressants.

Another academic study published in PubMed Central (PMC), the American National Library of Medicine claimed a 65% remission rate for participants suffering clinical depression in a trial of 27 participants undertaking a course of 20 yoga classes. This is good news because according to the Mental Health Foundation 20% of people in the UK get symptoms of anxiety and that’s up 15% since 2013. Statistics should always be taken with a large dose of (low sodium) salt, but those who completed the trial experienced significant reductions in depression, anger, anxiety, neurotic symptoms and heart rate variability. Iyengar yoga was judged particularly effective because its use of props makes it more accessible to beginners. Strict teacher training programmes make it safer, promoting holistic combinations of standing, sitting and backbend poses, with the most important inversions and final relaxation with breathing exercises (Savasana).

Being Upside Down is Good for your Head

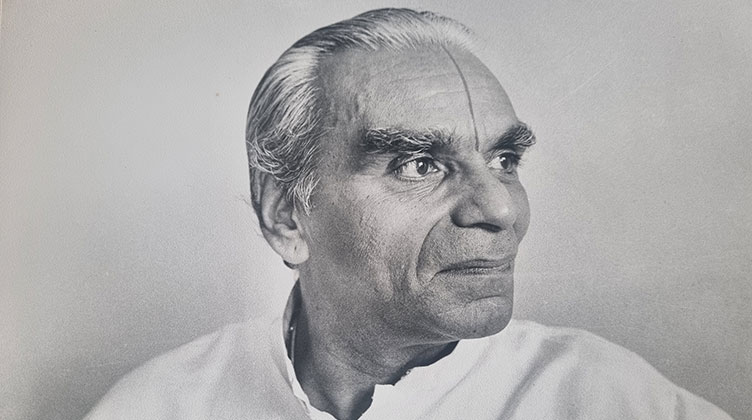

Roger Cole PhD who teaches Iyengar yoga in America and abroad is a specialist in the science of sleep and relaxation. He says that working on physical alignment brings mental and physical balance. He says inversions are particularly restorative. During inversions the rib cage is drawn by gravity towards the head allowing the lungs to expand and calming the vagus nerve that interfaces with the heart, lungs and digestive system. Cole’s specific area of interest is in the baroreflex which is responsible for keeping our blood pressure constant. Blood pressure falls when lying down and this response can be what he calls ‘super-charged’ by practising inversions. Here, BKS Iyengar explains the effect of inverted postures on the central nervous system and brain.

Moreover, inversions help moderate the production of the noradrenaline hormone which is meant to keep us awake during the day, but over-production of which is associated with stress and keeping us awake at night.

The physiological basis to yoga’s effect on mental health are not fully understood except on an empirical and anecdotal basis – which is to say by experience and testimony. Cole cites how at the age of 65 BKS Iyengar had the lung capacity of a 24 year old and how even in his 90s was still active and able to perform inversions. The experience of doing yoga is however all the evidence I need. Like anyone doing yoga regularly I have enjoyed the endorphin rush you can get without the ugly, joint-crunching schlepp round local parks or polluted streets. And I have experienced the calming effects of pranayama after an anxious day. It is worth reminding ourselves, moreover, what endorphins are – hormones that activate the body’s opiate receptors causing feel-good analgesic effects. It is in short your body’s reward system.

Cynics might say that means we are all junkies under the skin. But apart from the head rush especially associated with vigorous standing poses, there are many ways that yoga makes you feel better in mind and body. More than the blissed out benefits of pranayama breathing, there is the levity that comes from back bends, and the soothing effects of forward bends (I find them the toughest and most threatening to my lower back so I’m taking my teacher’s word for this). And hand-stands (Adho Mukha Vrksasana) are as close as you get to an instant hit of well being without resort to a crack pipe.

Iyengar Yoga as a Complementary Practice for Mental Health

No one is suggesting that people suffering mental distress should abandon medication and rush instead to the nearest yoga centre. For me yoga is rather a complementary practice that can run alongside the rest of your life. But there is little doubt that being good to your body can help you feel better in your mind. Beside which anti-depressants can have their own side effects such as nausea, weight gain, loss of libido, fatigue, dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, dizziness, agitation, irritability and anxiety. Yoga can have side effects too of course and it is possible to injure yourself doing yoga but only really if you’re doing it wrong. This is why you need a well-trained teacher. But I’ve yet to hear of anyone sustaining a mental health injury from yoga. Admittedly some yogis can be a bit pleased with themselves but their teachers should be telling them off: pride is not a path to enlightenment.

If all this sounds too earnest, there is the phenomenon of ‘laughter yoga’. Laughter opens your chest, connects you with others and gets you breathing more deeply. The full physiological benefit should perhaps be verified by randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, but until then you can make mine a Supta Baddha Konasana.

Yoga and Mental health: Dipika, Journal of Iyengar Yoga London, vol 52 (2020)

Blog categories

Become a member

Join our community to get reduced class prices, early booking for events and workshops plus access to the studio for self practice.

Recent news and articles

Iyengar Yoga Home Practice Videos with Raya Uma Datta

27 March 2025|

B.K.S. Iyengar’s visits to Ann Arbor, Michigan

20 March 2025|

Origins of the Modern Yoga Mat

24 October 2024|